Journal

The journal on portikus.de operates as an extension of the exhibitions at Portikus themselves. A wide spectrum of contributions including essays, interviews, fictional writing or photo- and video-contributions provide a closer look on artistic interests and reflect on topics that concern our society, politics and culture.

Ximena Garrido-Lecca, 'Inflorescence', Installation view, Portikus, Frankfurt am Main, 2023, photo: Jens Gerber

In 1956, the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda dedicated an ode to the corn plant. In this solemn poem form, he praised the metamorphoses of the grain and its influence on the human condition. The “green lance”, later covered by “golden corn”, is a symbol of the salient and precious plant, but also a reference to the changes in corn culture due to colonization: a weapon always means defense and pain – and gold awakens greed. From the 16th century onward, Spanish chroniclers reported supposed landscapes of gold in their accounts of Central and South America. But they had misunderstood the pre-colonial narrations, whose description referred not to the precious metal, but to cornfields. Even today, graffiti murals in Bogotá’s urban landscape address this misunderstanding of the golden landscapes, illustrating that wealth as a monetary value is based on Western world views and thus deviates strongly from Andean ideologies.

Already in the second paragraph of his Ode to Maize, Neruda formulated a temporal reversal when he admonishes himself to emphasize the “simple grain in the kitchens” instead of the “history in the shroud.” In Inflorescence, her exhibition at Portikus, the artist Ximena Garrido-Lecca (*1980, Lima) starts precisely there, in the kitchens, the everyday, and carries out a change of perspective that already resonates with Neruda. Over the two floors at Portikus, the cultural significance of corn plants can be traced from different perspectives. In doing so, the artist emphasizes how Central and South America, the regions of origin of corn culture, were often not given enough consideration in history and works against the tendency, dominant in colonial chronicles, to overlook the history of development of local plants and thus devalue the agricultural skills and achievements of indigenous cultures.

Ximena Garrido-Lecca, 'Inflorescence', Installation view, Portikus, Frankfurt am Main, 2023, photo: Jens Gerber

The flowering period of corn plants in Central Europe lasts from July to September. The grasses and cobs are harvested until late October. For her exhibition at Portikus, Garrido-Lecca responds to the local conditions of the crop plant, exhibiting it in a variety of forms. Whether plants standing upright in bundles or leaning against the wall, corn cobs sturdily set in metal frames that serve as seating, or a wall box filled with dried cobs, corn is the main motif and material of Inflorescence and thus serves as a means for the artist to reflect on the mutual influence of man and nature. The sculptures of bundled corn plants are topped by antennas, as they are known from telecommunications. Sticking out of the bundles, it appears as if they were part of the drying process themselves. Technology and nature can no longer be separated, but rather merge into one another. The challenges resulting from this neo-colonial entanglement are likewise discussed by the many voices that are part of the radio broadcasts accompanying the exhibition, and deepened with ecological, social, biological as well as political aspects: The desire for diversity of varieties and ecological cultivation measures on the one hand, and the ever-growing spread of genetically modified corn1 on the other hand, is a paradox whose magnitude becomes tangible as one listens. The antennas thus symbolically stand not only for global networking, far-reaching communication, and knowledge transfer, but, in their relationship to corn, also for clinging ambivalences. Partly radiant, sometimes lattice-like, their shimmering rods suggest an anthropological imbalance and from a material point of view it is evident that the aluminum will outlast the plant.

Ximena Garrido-Lecca, 'Inflorescence', Installation view, Portikus, Frankfurt am Main, 2023, photo: Max Creasy

The displaced temporality of nature and technology in capitalism also becomes clear in relation to the traditional use of corn in everyday life. Five thousand years ago, Mexico and Peru were the first countries and regions in which corn was domesticated. Since then, it has been deeply inscribed in the cultural history and culinary culture of both countries: Mexico, for example, is known for its corn tortillas, Peru for the nutritious cold drink chicha de jora, made from fermented corn. Aspects of these processes are materialized in Inflorescence through a millstone, or bowls, plates, vats, and jugs scattered throughout the floors. These utilitarian objects represent an ongoing practice of corn processing and incorporation as part of a present in which Latin American farmers are politically engaged in preserving their communities’ traditions, seed diversity, and the right to food sovereignty. Communal forms of organization, which have increased in recent decades, are resisting oppressive dynamics.

Ximena Garrido-Lecca, 'Inflorescence', Installation view, Portikus, Frankfurt am Main, 2023, photo: Max Creasy

Germany, on the other hand, cannot claim a tradition of maize cultivation. Only since the 1970s has corn been grown there on a large scale – mainly as a raw material, e.g., for animal feed, bioethanol, or glue. By detaching the corn from northern Hesse from precisely these processing methods for her sculptures, Garrido-Lecca links local and global aspects of the exhibition site, such as transport routes or seasonal conditions, and highlights the immense cultural and historical differences in the use of natural resources.

The geographical and temporal lens of Inflorescence helps navigate the postcolonial discourses surrounding corn. These include the question of territories and claims of ownership, but also the appropriation of cultural and culinary traditions built on corn as food. The artist’s arranging and staging of the plants and cobs is thus centered around the transhistorical and transcultural meaning of corn, which is largely ignored or not listened to in everyday life in Central Europe. This is one of the reasons why Garrido-Lecca equips the North Hessian corn plants with megaphones that acoustically occupy Portikus with a constant boom. As evidence of the millennia-old corn culture and its affiliation, a steady Morse code sparks a narrative from the Mexican Mayan culture into the exhibition space, stating that humans are descended from corn. But for the content to be identifiable as such, a key to understanding is needed, otherwise the morse content remains merely a background noise.

Ximena Garrido-Lecca, 'Inflorescence', Installation view, Portikus, Frankfurt am Main, 2023, photo: Max Creasy

Franciska Nowel Camino is an art historian and currently a research assistant and doctoral candidate at the HfBK Dresden. Her research focuses on the postcolonial reception history of Andean textile techniques. She studied art history, Romance languages and literature, and archaeology at the Goethe University Frankfurt am Main and worked in the Städel Museum’s Graphic and Digital Collection as well as at Frankfurt’ Curatorial Studies - Theory - History - Criticism program. Her texts have previously appeared in anthologies, exhibition catalogs, online magazines, and AKL.

Log Diversion

SEPTEMBER 22

A person and I were sitting at the wooden table downstairs when they asked me what’s happening in this room and I reply not intentionally repeating the question and also adding another one to see if they’ve read the newspaper or not I wanted to start the conversation asking what was their favorite part of it if there was one usually there is one but they reply I'm coming from my reading group my favorite activity they’ve said so I can't read anymore I'm blind I'm old but I will do it tomorrow or when I'm able to see again I'm going to rest my eyes the rest of the day so I went back to their question and walked with them to the water station they talked about seasons and I felt that’s all we talk about in the transition between one and the other but especially this one maybe in the north hemisphere after they have tried the river and said that in a warm day that could second them they will not doubt getting wet feet upstairs we said goodbye goodbye

SEPTEMBER 20

A boy came with a bag of chestnuts and asked if he can put one of them in the river and play with it. Later in the afternoon a friend came to visit the show with a chestnut too. It’s the season now. When the sun shines in during sunset, it leaves marks of shadow and light on the wall not seen in those summer months. Very soon this temporary river in Portikus will be gone, leaving stories behind like chestnuts falling from trees in autumn. - YX

SEPTEMBER 17

I was asked to make photos of the visitors three times today. It's such a simple and andom fact about today's shift but it made me think of how each time all of them were photographed with a different river in the background. Because it's flowing, it's everchanging, it's never the same water. - HL

SEPTEMBER 16

A river flow down each cheek of the visitors today because it‘s raining. The proud mother of a swimmer came to follow his tracks. Someone ask me what are the biggest flows of water I have seen? - HS

SEPTEMBER 13

The water stream has changed its colour today, wearing silver on its ripples. The blank skies and reflective waves, along with the bluish tree leaves are directing my mind to play out the Twin Peaks theme soundtrack in my head over and over, and I can’t help but listen to these synths as i stare at those trees. - RA

SEPTEMBER 11

Today is the 800th anniversary of Alte Brücke! Happy Birthday! - MG

SEPTEMBER 10

Portikus was a shelter for people when it rained. - ES

SEPTEMBER 9

Today Barbara visited us again - don't know exactly how many times she has already been to the exhibition but it was already the second time we saw and talked to each other: about Berlin and the Berlin Wall, how it was for her to grow up near the border of Germany, France and Switzerland, how as a kid she would go into the water whenever possible…And suddenly I've spotted a quirky playful smirk in her eyes - 'ich habe eine Idee!' . And the next moment she started folding the small paper she took out of her bag into a paper boat, doing it so quick and professionally as if she makes those every day. The boat's life was short but glorious. Barbara promised to come back with a toy boat next time. - HL

https://drive.google.com/file/d/12Mx2MxsZ5JK2MLioIAOiR-oV1aKdlto6/view?usp=sharing

SEPTEMBER 8

I dipped my toes into the water with a stranger. - ES

SEPTEMBER 7

Clouds took over the river today, leaving it greener in contrast. I had a nice conversation with a lady who stumbled upon the waters and decided to see it for herself. We spoke about swimming friendly bodies of water and I learned about an ancient one that still has the built stairs and traces of people back in the day. Added to my list of things to see in frankfurt. - RA

SEPTEMBER 6

The sun left its mark in the hall, forming a long line of squares on the floor. It was a bit distracting to look at. A couple of old men walked in, curious to look at the water and thrilled when finding out that they could walk in there. One of them transformed into a child the minute his feet touched the running stream. He said as he was leaving with excitement: it’s a blessing! - RA

SEPTEMBER 4

Today we had Martin Scheuermann from the company who printed the newspapers visit the show with his wife. E and I made an effort to show them around and make them feel welcome. They emphasized that they enjoyed the exhibition and the whole message it sends. First they were hesitant to get into the water, but they adjusted really fast and said how refreshing it felt. They also drank the water downstairs. He said to give a special thanks and compliments to C & L. - MG

SEPTEMBER 3

We found traces of the passing summer in the water. - YX

SEPTEMBER 1

Today the sun was a rare guest in the gallery. As if somebody adjusted the light settings and suddenly the world around has lost a bit of colour and saturation. It also does something to the water although it is transparent. I don't really believe calendars but looks like September likes to be punctual. - HL

AUGUST 30

A woman told me the story of how she grew up opposite the island where Portikus is, looking at the building that existed before it and wonder whether it was a church or a windmill or something else. Then she moved away from Frankfurt. And today she visited Portikus for the first time and tasted the river.

Now the wind brings in fallen leaves too. - YX

AUGUST 28

Since the festival is still going, there are a lot of visitors coming in and out. Our river is a place for them to relax and take a breath. - MG

AUGUST 27

The most common question I've heard today was 'What's going on here?' ('Und was ist denn hier los?'). Yeah, exactly - it's GOING (also running, streaming,changing, rushing, moving etc.) and it is already enough information about this artwork. This was the answer I had in the back of my mind but I never said it out loud. - HL

AUGUST 26

Everything is painted grey today, from the water of the Main to the floors of the Portikus. After yet another brutal heatwave last week it has finally cooled down, and the wind is whipping jitters into the river. Very likely also the reason less people feel the desire to step into the water. - NL

AUGUST 25

As one of the visitors was surprised by the temperature of the water (she didn't expect it to be so warm), I thought of how surprising it actually is - barely a week before September kicks in. In the pagan tradition (or at least in a Slavic version of it as I'm aware of), you're not recommended to enter any streams, rivers or lakes after August 2 because from this day on the waters are occupied by devilry and other dangerous creatures and the season of cold rainy weather starts. Seasons have changed greatly ever since and the waters can be cleansed by the human. Guess our ancestors would find it very safe but not as exciting anymore. - HL

AUGUST 24

A man with big green Aldi bag coming in with a calming smile. He looks like he is on his way to grocery shopping. Then he sat down by the river, closed his eyes, crossed his legs and started chanting. A quiet afternoon. - YX

AUGUST 23

Two friends entering the water together. After some minutes they hugged each other with their feet still in the water. - ES

AUGUST 21

The mystery foam is still appearing in the bucket. The mystery of foam remains the mystery after the two sunny non-even-close-to-rainy days. I would call this foam a 'cloud' - giving such a poetic name should eliminate the visual ugliness and disgusting smell this foam actually has. The foam of mystery is what I created in my head while looking at a pathetic smelly gathering of bubbles appearing as a result of intense waterfall. - HL

AUGUST 20

Today we had a couple visit us who were blind. I helped them find their way. Once they were in the water, H and I discussed how most art is not accessible for everybody. Here we had the chance to create an experience for them that went way beyond a visual reception. I am very thankful to be a part of this moment. – MG

AUGUST 19

A lady with a mysterious smile came in. Our conversation started with her asking the gender of the artist of the show ( she is the first person asking me the question). Then we began to talk about tenderness, theology and Rudolf Steiner (and many more). The water carries the story and goes on. - YX

AUGUST 18

I discovered that a pigeon has made a nest underneath the bridge, a butterfly flew through the front doors and then out again. I check the duck eggs in a nest on the island from the door in the basement. I’m now becoming more familiar with the small parts of nature which inhabit the island. – ES

AUGUST 11

did you ever see anyone washing clothes in this river? – NN

AUGUST 2

Towards the end of the day, just before our river was supposed to stop flowing, Francisco told me that someone had vandalized our toilet. At first I thought he was joking with me, referring to the Wallace Stevens poem affixed to one of the doors, but then he showed me a bright green sign in the other cabin. We tried to decipher it, but didn’t get far. Maybe someone didn’t want the river to stop flowing or wanted to challenge our water’s ability to remove graffiti. - CB

JULY 31

First shift data

Water level: 153 cm

Water temperature: 24,8 *C

Number of visitors: 231

- MG

JULY 30

The sky is completely clear today and hot air is filling the room. I saw a family come in with their child. They helped the child walk in the water, holding hands and laughing together. It was a very beautiful moment to witness. - MG

JULY 26

I sat close to the riverbed and got lost in the rushing of the water until I was told the apodictic sentence that this wasn't the real Main. I was a bit surprised and asked for the real one. We went to the window and he pointed to the water flowing around the Main Island. I asked more questions, interested to know what and where the real Main is. At one point I told him that I lived in Offenbach and that I liked sitting at the lock and that the surging water fascinated me. In doing so, the visitor began to sway, the artificial interruption of the Main undermined his view of the real Main. We were silent for a moment. I then sat down again by the riverbed - and the visitor sat down with me. - NF

JULY 24

The sun is really strong today. Being in the water feels even more refreshing than it usually does. I ended up talking to a visitor for an hour. Somehow the conversation transformed from the phobia of swimming in natural waters where the floor is hidden in the dark, to discussing cyber security and the impact of social media on our everyday lives. - MG

JULY 15

A woman told me today that there’s a waterwork in Schwanheim that also purifies the Main water and serves it to its guests. I wonder if they also show us step by step how they filter the water…

Anyway, there was a huge family visiting the exhibition today and RA and I had interesting conversations with them of course about rivers and bodies of water. They told us about a black river in Syria. - RH

A women came to me asking me about the stones that we use for mineralizing the water. It turned out she is a jewelry designer and has a lot to share about how stones bring different energy to the substance they are in contact with. I enjoyed this moment of exchange. - YX

JULY 9

Towards the end of the day a cloud gathered, and the air became close as if a storm was about to break, it turned cold. The water running through the space kept a warmth, which surprised visitors as much as it did me. - ES

A glimmering surface seduces when walking past Portikus on the bridge. Lot’s of visitors throughout the early hours of the day. Conversation flowed in many different directions, from aquatic monkeys to horses dragging pilgrims along the main. Today, our miniature Main felt like a ceremony, I don’t yet know of what. - AS

JULY 8

The thick weather pulled people in today. They came in waves, mostly in groups. I found myself having conversations almost constantly in water. The skin on our feet like raisins. Two smaller persons and I were playing wild in the water for quite a while. The water was the best they ever tasted, they said. Tasting mineraly, a characteristic taste, of it’s own, flowing through us at that moment. - AS

JULY 3

Today‘s information about the water:

Total hardness: 0ppm

Free Chlorine: 0ppm

Iron: 0ppm

Copper: 0,5-1ppm (above average level)

Lead: 0ppm

Nitrate: 0ppm

MPS: 0ppm

Total Chlorine: 0ppm

Fluoride: 0ppm

Cyanuric Acid: 0ppm

Ammonia Chloride: 100ppm (above average level)

Bromine: 0ppm

Total Alkalinity: 0ppm

Carbonate: 40-80ppm (below average level)

Ph: 7.2-8

RH

JULY 1

I had a conversation with a person that comes from Spain, Catalonia and lives near a river where you can drink the water since it’s so clean. I was several times in that region, close to a river called Muga where I could drink the water, too. We had a connecting moment while we both we‘re standing in the Main. - RH

JUNE 30

I learned about the de-humidifier today. We have to always keep it running and we’re emptying it in the mornings and evenings. The ventilators have to stay on too. The de-humidifier is preventing the walls in the gallery from getting moldy. When I imagined the mold on the white walls I had to think about how it would look if the walls had been layered with actual moss, with creeper plants and ivy. - RH

JUNE 29

Noticing the pipes shudder with the flow of water it directs. The pipes are as if they were the intestines of the show. A young child runs through the water. Later some visitors are curious about the engine, pumping the water up, so I take them outside to show them the heart of the work. They were in Frankfurt from LA. - ES

JUNE 28

Upon inviting a visitor into the water with me he quickly takes off his shoes, steps into the water and takes a deep breath while closing his eyes. - MG

JUNE 26

It's warm in Frankfurt, almost 30 degrees. The banks of the Main are well frequented. In the direction of Offenbach it gets quieter. If you take your time tomorrow, you will see the water changing its colors: A visitor drew my attention to the fact that the many colors a river takes on and can take on over the course of the day are rarely emphasized. The color changes with every minute, with every wave. I've been told that those who are susceptible don't need a treasure map. I'll sit down at the Main tomorrow. - NF

JUNE 25

The river pulled many people into space today. I only realise how the sound bounced all around throughout the day when I finally meet the silence at the end when closing. Outside the streets were littered with people which spilled into the space. The footfall was faster than the river. The air was warm, around 25 degrees, yet the gallery stayed fresh. For that freshness, I am grateful.

JUNE 24

Opening day. Heavy rains and thunder from 18.00 rounding up a hot and mostly grey day. 26 degrees most of the time. The low pressure making the water feel even warmer. Doors and windows open on both sides of the gallery creating a counter stream of air to the water flow. Successful event. - HS

JUNE 23

The fresh air around Portikus is stolen again, smells like rain with thunder but weather tricks us over and over. Our local tiny Main had a lot of visitors today, as soon as they put their feet into the water the gallery started to remind me moreand more of a children's playground. The buzzing sound of chatting and laughing backed with the sound of a water flow till midnight and some time after. - HL

Orange peels, drying in the Portikus garden

JUNE 22

It’s very nice today. I peeled oranges and lemons. My hands are still smelling like them. It felt very meditative to peel in stillness in the garden. The set is coming slowly to an end. I am excited for the opening. I was singing before with AS to lyrics that AR gave us. It felt very nice to sing. - RH

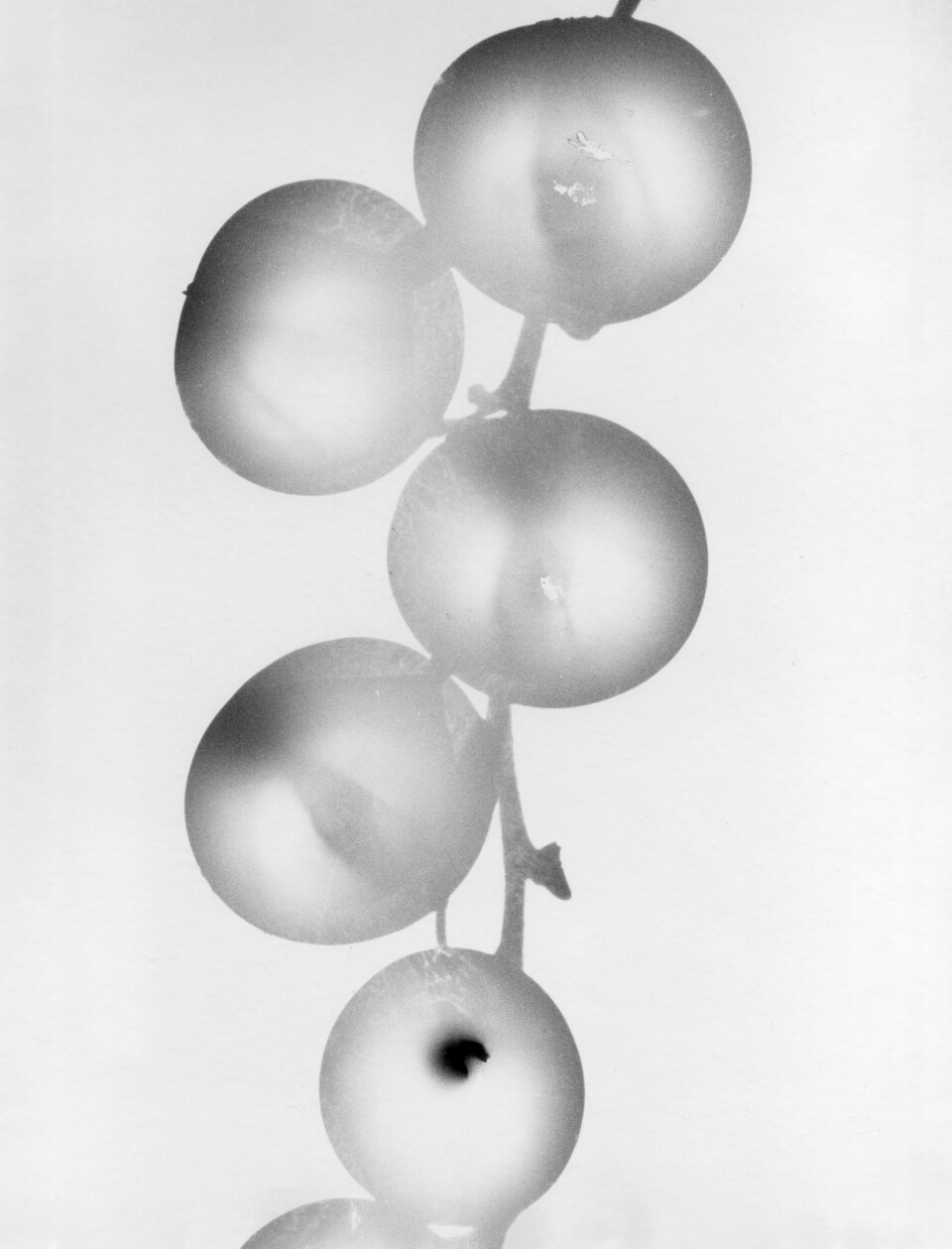

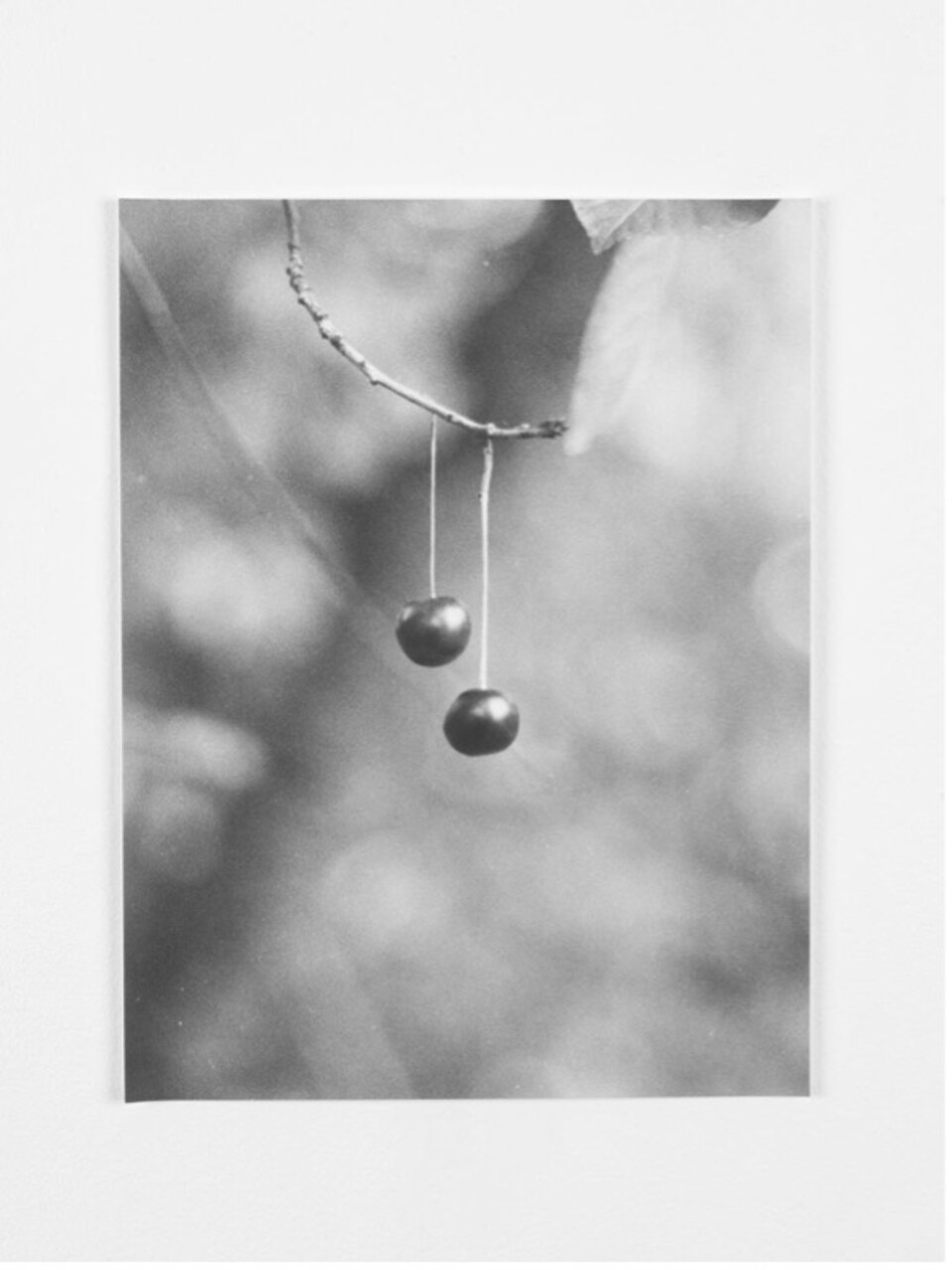

Jochen Lempert, Johannisbeeren, 2019, © Jochen Lempert/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022. Courtesy: BQ, Berlin, and ProjecteSD, Barcelona

No one is more thoughtless than a lemming, more deceitful than a cat, more slobbering than a dog in August, more smelly than a piglet, more hysterical than a horse, more idiotic than a moth, more slimy than a snail, more poisonous than a viper, less imaginative than an ant, and less musically creative than a nightingale. Simply put, we must love—or, if that is downright impossible, at least respect—these and other animals for what they are. 1

— Umberto Eco

Jochen Lempert’s photographs begin with an encounter, the occurence of his meeting with plants and animals, real or artificial representations in urban or rural settings, museum displays, scientific books or on the clothes of a passerby. Flora and fauna in his images appear to interact, tilting to address his camera, or behave completely indifferent to his presence. These images have earned Lempert recognition as an artist interested in the way the natural world becomes present to us. Once photographed, these seemingly unexceptional encounters of the everyday become magnificent bearers of revelations that range from portraying the mischievous nature of animals to the majestic shadows cast by sun-kissed foliage. There is an ease to Lempert’s images, a proximity that speaks to his comfort around the smallest of insects or frazzled of birds whom, in turn reward us with access to their existence. In his work, similarities between organisms, and celestial or terrestrial phenomena are looked upon with emotional intelligence and become the starting point for images that reveal the interconnectedness of nature. His interest in scientific disciplines, especially biology and animal behavior, translates into depictions of metaphorical, associative, and political acumen that allow us to look, almost intimately, at other species with whom we share life on this planet.

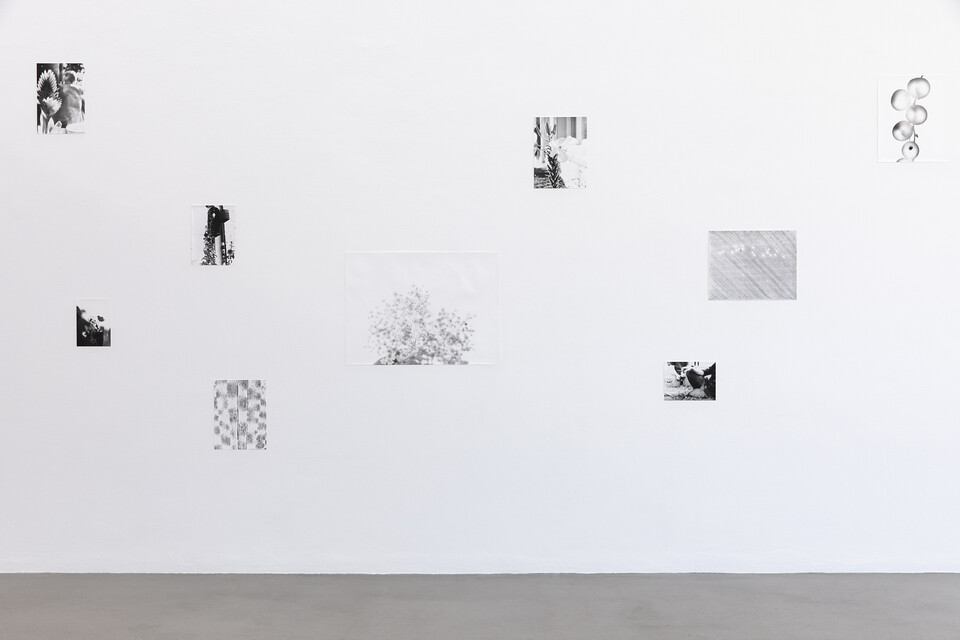

Jochen Lempert, installation view, Portikus, 2022, © Jochen Lempert/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022. Courtesy: BQ, Berlin, and ProjecteSD, Barcelona; photograph: Diana Pfammatter

For three decades now, Lempert has pursued with remarkable consistency and inventiveness the basic idea of only making images according to a principle of necessity. Although he is known for constantly carrying a camera in his coat pocket, for him the act of making an image only happens long after the initial click of the shutter. The bulk of his work does not originate from contact sheets, but rather he selects directly from negatives, often only using a third or less of the images in a roll. Through working prints, which he makes in A5 format or smaller, he shuffles and studies different variations before committing to a specific size, crop, or light. One consequence of this meticulous process of editing is how the act of seeing itself becomes the subject of the work and his method of display. Each of Lempert’s works is the sum of gradual decisions that lead to the appearance of an image. His photographs, primarily gelatin silver prints, are developed in analogous color schemes of gray on bright white matte Baryta paper that he handprints in his studio and when exhibited are left unframed and taped directly onto the wall or placed inside vitrines. Whether making an exhibition or a publication, Lempert prefers to seamlessly integrate older and newer pieces thus creating a body of work of close interdependence and one that is deliberately anachronistic and where decisions on pairings and grouping are interposed and reformulated by a relational drive. This associative approach to the work of art is similarly evoked in the titles of his works, favoring single nouns or descriptive sentences that aim to spare the viewer of unnecessary distractions and ground the image experience, in the artist’s own words, to what one “strongly feels in the moment of seeing.”2

Jochen Lempert, Schmetterlingshafte, 2019, © Jochen Lempert/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022. Courtesy: BQ, Berlin and ProjecteSD, Barcelona

In the playing field of contemporary art, Lempert is a blessed outsider. He began exhibiting his work in Cologne and Hamburg in the early 1990s, and except for the occasional thematic group exhibition, it has circulated primarily in the quartier of photography although regarded at times with suspicion given his unconventional use of the medium. Lempert´s simultaneous embrace of different photographic procedures from instantaneousness to mise en scène, which he reconciles through the recurrent use of multiples in sequential order, allowing the work to withdraw from usual categorizations. Another curiosity surrounding the public reception of Lempert’s practice, and particularly his use of the 35mm camera, has been a recurring reference to the artist’s scientific credentials. His name is typically accompanied by titles bestowing him an additional level of exceptionalism: biologist, odonatologist, entomologist, or ornithologist. Although it is no secret that from time to time he has authored scientific reports, how remote these studies are from his work is confirmed by their total absence in his displays and monographs. That such classifications should be of concern for the artist is rather unlikely. Lempert is not much interested in demonstratable facts, nor is his working process ruled by fixed structures or theories, but rather an open system where, as he observed, “searching is a big part of the whole project” and where unlimited outcomes are plausible every step of the way. 3 In his photographic work, Lempert is actively silent regarding the natural sciences. Rather than applying his scientific knowledge to what he photographs, he visually invites meaning through the act of seeing−the act of seeing what is depicted and what awaits to become visible.

Another striking aspect of Lempert’s practice is his studio or rather the walls in it, which exhibit a vast number of tiny cavities from the thumbtacks he uses to pinup working prints. Trailing on various directions, the marks show decades of his looking en route to finding an image. The placement of the prints on the wall alternates between single photographs, symmetrical groupings where prints of the same size are paired into duets, quartets or two-tier grids spaced only a few centimeters apart, or they are arranged as asymmetrical pairings where different scale prints are placed in dialogue but kept at arm’s length distance from one another. The various combinations and configurations enacted in the studio influence the improvisations played out on the walls of the exhibition space. But this is only one aspect of his quest, another crucial part of the process happens inside the darkroom prior to the arrival of a print to the wall. The artist has explained it this way: “It is actually always about seeing something from the photo or seeing something in the photo. Sometimes you need several pictures to make something come together. And sometimes only one is enough.” 4

Jochen Lempert, installation view, Portikus, 2022, © Jochen Lempert/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022. Courtesy: BQ, Berlin, and ProjecteSD, Barcelona; photograph: Diana Pfammatter

If the wall is a stage where Lempert conducts rehearsals, the small cardboard boxes overflowing with test prints sitting on the shelves are the casting auditions. Hundreds of prints the size of index cards are grouped into collections, classified by single words in German handwritten hastily on sheets of paper that read, for example: H2O, horses, only bees, pigeons, plants, skies, wind. Others have more metaphorical categories alluding to specific constructs such as: picture logic, symmetry, senses, and Gestalt. Lempert’s working print collection functions as more than a simple repository; it has become a lexicon that he employs, borrows from, and modifies to generate what he calls “constellations”−a mode of display where the sequence of works establishes a dialogue on a wall or through an entire room. If the preliminary working prints provide him with answers on which image should be kept, the resulting groupings expand on his construction of meaning through juxtapositions and comparisons. Lempert proceeds intuitively through hypothetical placements and differentiates images according to no preconceived plan. Hence, all scenarios are provisional, out of chronology and subject to the fast surprise of an appearance. Although there are pairings that emerge through his use of improvisations, every installation he makes of his work is site-specific, that is, staged on-the-spot and poised to generate understanding precisely in the fleeting and interchangeable meanings that reside permanently in the present.

At the heart of Lempert’s work is a radical ecology that is characterized by a practice of mind, hands, and eyes. Through the use of images, where the world is not a place to be captured but a terrain of correspondence, he makes visible encounters with nature and nonhuman beings where transmission and coexistence occurs. Lempert’s approach to the natural world while fearlessly up close to it is cordial and respectful, but above all, empathic. His images deliver lessons not on what to look at but on how to see and consider the species with whom we coexist with on this planet. Likewise, his interaction with the surroundings is replicated by his search for relationships. For Lempert, photography does not necessarily replace the experience of the natural world as nature in absentia but visualizes it as presence. Our perception converges with Lempert’s intimate proximity to his subjects when we join him in the affirmation of the dignity of all living beings. His overlapping interests in art and science converge in his work not as depictions separated from the world that we inhabit but rather belonging to it, thus rendering photography as foliage of the human experience.

In the framework of his exhibition Pierre Verger in Suriname Willem de Rooij invites the artists Razia Barsatie, Ansuya Blom, Ruben Cabenda, and Xavier Robles de Medina to show their works on the Portikus website. With the program Flux und Reflux – A Selection of Moving Images Portikus' audience is introduced to moving image made by four contemporary artists who have a relationship to Suriname. The video works will be online for two week at a time:

24.06.–07.07.2021

Ansuya Blom, SPELL, 2012, 6'38

SPELL is a short film documenting the thoughts of a man in a state of unreality. Sounds invade his thoughts, get amplified and mix with associations from his past. In this in-between world he tries to regain his grip, contemplating early beginnings and simultaneously mocking his own state of being, the futility of action and the rituals of daily existence.

The images for this film were photographed in the house of Theo Van Doesburg in Meudon, France during a residency in 2010 - 2011. The words of Franz Kafka speak for themselves and it was their strange mix of humour and despair that attracted me. (Ansuya Blom)

Ansuya Blom (*1956 in Groningen) lives and works in Amsterdam. She studied at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague and Ateliers '63 in Haarlem. Blom has been working in various art forms, including drawing, painting, photography, film, text, collage and sculpture, since the late seventies. In 1981 she received the Dutch Royal Award for Modern Painting. Her films have been screened at the International Film Festival Rotterdam, Rencontres Internationales Paris-Berlin, IDFA Amsterdam and at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Her work can be found in the collections of museums, including the EYE Filmmuseum, Tate Modern, Stedelijk Museum and the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen. Solo exhibitions include Camden Arts Centre in London, Douglas Hyde Gallery in Dublin, Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and Casco Art Institute in Utrecht. In 2020 she was awarded the Dr. A.H. Heineken Price for Art.

Blom also holds a master's degree in psychoanalysis from Middlesex University in London and is an associate member of the Centre for Freudian Analysis and Research in London. She is an advisor at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam and was a guest advisor at art institutions in the United Kingdom, South Korea, Surinam and Indonesia in 2019. She has given public lectures and interviews most recently at the Nola Hatterman Art Academy in Surinam, EYE Film Museum, Casco Art Institute and De Appel.

Upcoming artists in this series:

01.07.–15.07.2021

Razia Barsatie

In the framework of his exhibition Pierre Verger in Suriname Willem de Rooij invites the artists Razia Barsatie, Ansuya Blom, Ruben Cabenda, and Xavier Robles de Medina to show their works on the Portikus website. With the program Flux und Reflux – A Selection of Moving Images Portikus' audience is introduced to moving image made by four contemporary artists who have a relationship to Suriname. Die Videoarbeiten werden jeweils für zwei Wochen online verfügbar sein:

10.06.–24.06.2021

Xavier Robles de Medina

Ai Sranang, 2017

Music: Lieve Hugo, "Oeng Booi" and "Blaka Rosoe"

According to the Transnational Decolonial Institute, decoloniality endorses interculturality, “the celebration by border dwellers of being together in and beyond the border.”

Ambivalence is the true sentiment of the “diaspora”—as much as we hate to admit it, we love the feeling of being recognized, not as celebrities but as part of a “lineage,” as extended family. Jill Casid writes that “while, since the nineteenth century, diaspora has been used to refer specifically to the dispersion of a people, imagined as a tribe or family unit, diaspora also signifies the scattering of seed.”

Stuart Hall has also interrogated the term noting its meaning is rooted in colonially constructed binaries, of the “original” and the “copy,” and of “inside” and “outside.” It’s telling that our national flower, the Fajalobi, is only a recent transplant from India.

(Extracts from Xavier Robles de Medina's essay “Preface”)

Ai Sranang is a short montage film that examines Surinamese history and politics since its independence from the Netherlands in 1975. Through its fragmentation, the montage alludes to the complexities of diaspora as it stands in relation to identity. The tropes of in-between-ness and travel are an extension of this metaphor, yet they recall also ideas of leadership and government. The image of a “swinger” bus completely running amuck by a reckless driver extends its metaphoric space beyond the Surinamese context to the events that have defined a more global neoliberal era. Robles de Medina has been building an extensive collection of found images that is central to his artistic practice as he appropriates, edits, re-contextualizes and transforms them.

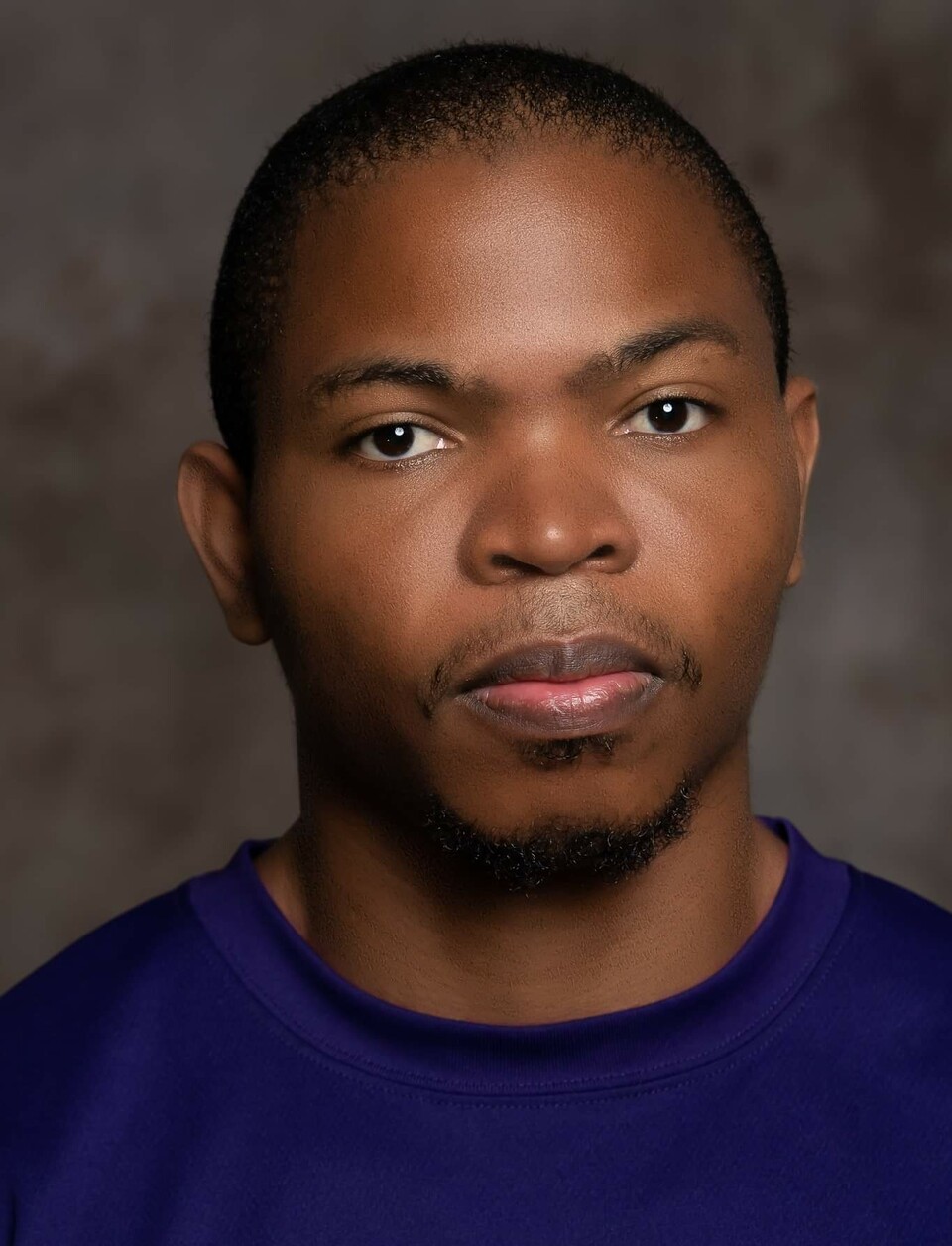

Xavier Robles de Medina (*1990 in Paramaribo) is a visual artist based in Berlin. He graduated from Goldsmiths, University of London. In 2015 he was nominated for the Prix de Rome Visual Arts in the Netherlands, and was shortlisted for the Dutch Royal Award for Modern Painting. Recent solo exhibitions include SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah, Another Mobile Gallery in Bucharest, Praz-Delavallade, Los Angeles and Paris, Readytex Art Gallery in Paramaribo and Catinca Tabacaru Gallery, New York. Robles de Medina has been selected to participate in Senegal's fourteenth Dakar Biennale in 2022.

Portrait image: Sascia Reibel

Website: http://xavierroblesdemedina.com

Upcoming artists in this series:

17.06.–01.07.2021

Ruben Cabenda

24.06.–08.07.2021

Ansuya Blom

01.07.–15.07.2021

Razia Barsatie

For Cashmere Radio, Hajra Waheed spoke with Reece Cox about her work Hum, which was present in her solo exhibition at Portikus from 11.07. bis 06.09.2020.

This episode of INFO Unltd takes a deep dive into HUM, a recent sound work by artist Hajra Waheed. Exploring histories of sonic resistance across South and West Asia and North Africa over the last half-century, HUM reveals moments when sound and voice have united oppressed peoples and movements across geographies and generations.

Listen to Hajra Waheed on HUM and Abolitionist Modes of Listening

On the occasion of Arin Rungjang's exhibition Bengawan Solo at Portikus, Paula Kommoss speaks with the artist about the genesis of the work and the meaning of the river Bengawan Solo.

PK: What really interests me, first of all, is how did you come to find the singer for your work Bengawan Solo?

AR: A while ago, I was in Yogyakarta [in Indonesia] and had started to do research on Diponegoro, the priest to the Sultan of Yogya who is depicted in a painting by Raden Saleh. Raden Saleh was an Indonesian painter who fled from the country because of political aggression between the Dutch administration and indigenous Indonesian monarchy during the mid-19thcentury. Saleh went on to study Western painting, and his style was inspired by Delacroix, for example, which you can see in his compositions, use of lighting and so on.

Of course, all of this has been studied, and here I was wandering around in all this history about Yogyakarta and Indonesia in general, and I was also looking at the Chinese communist movement in Indonesia and so on. So, I had done all this research, and then I kept thinking about my relationship to Indonesia in general, which is always my starting point to making work. But I couldn’t find a very real connection to this material, except with the song ‘Bengawan Solo’, which I began to see would be my point of departure.

The first time I heard ‘Bengawan Solo’, I thought it was a Chinese song because I didn’t realise it hadn’t been written by the Chinese woman who sang it in 1960s. In a sense I had taken the Indonesian away in my mind. The song was really important personally because it was connected to a time in which I was questioning my sexuality, I was gay, I was not that gay, I didn't know what I was. I fell in love with a guy because of this song – it was a very romantic period for me.

I had the song in my mind for a very, very long time – stored in some part of my brain and my memory and then, even before I came to Indonesia, I discovered that the song was not by the Chinese woman after all, but that it was an Indonesian guy who wrote it in the 1940s, when he was only 19 years old. He had quit school and was working in a Kroncong band, the traditional Indonesian band that you can see in the video. And so, he created ‘Bengawan Solo’, which became incredibly popular. When Indonesia came under Japanese occupation [during the second World War], two years later, the song spread throughout Japan. There was a Dutch woman who was born in Indonesia but grew up in a Japanese internment camp, and she knew the song because it was played by the Japanese. It became stuck in her memory too, and so she sung a version of it as a teenager in the 1960s, which became really popular in Singapore and in other parts of Asia. So that was the song, and all these stories that are part of it became part of my knowledge, too.

I then got to know Rochelle – who sings this version of ‘Bengawan Solo’ – through a mutual friend. At that time, I was looking for someone who could imbue the song with more meaning beyond my own personal memories, and to share the song and its resonance with that person. So, my friend introduced me to Rochelle, a singer in a Kroncong band. Before we met, I didn’t know that Rochelle was the daughter of Lendra, a very important poet, or that her mother was a Princess, one of the daughters of the Sultan of Yogya. I was just looking for a singer who could deliver this song and share in its meanings. We met and got to know each other, and I learnt about her personal memories and history and so on, and it was so great – that there was this connection that I didn’t expect to find. I mean, I guess because things are always in circulation, things are always just there, even if it’s happening through different times. And so, the work is also about these layers of histories and memories and what we couldn’t foresee.

Actually, I didn’t need to put all that information onto the table in the show, it was just a way to display my research. For me, it’s enough to look at Rochelle singing that song and think of all these things that were happening before, before the song became so evocative for me. Like the Chinese using the river as a way to transport dead bodies during the Communist regime, and also Mushagra, Diponegoro, Raden Saleh’s painting, and all of these narratives that were in circulation through history, through art, and through memories – that’s what I think is so rich and thought-provoking.

PK: And the great thing is that all of these stories are brought together through the song ‘Bengawan Solo’, which tells the story of the legendary Solo River in Java, the island’s longest, in a really poetic way. The river is both the song’s main narrative, flowing from mountains to the sea, but also its title. So, on the one hand the lyrics lay out this seemingly simple story, but on the other, there are all these layers of narratives that you have just described: that the song comes historical connotations of the Japanese occupation, and something you mentioned earlier, that during the Communist regime, the bodies of those murdered by the state were washed by the same river. These stories are often violent but the song is beautiful, and whether you speak the language, or you don’t, a song is always a way to reach out to people.

AR: Yes, and so much spirit…

PK: …and to trigger emotion in a way.

AR: Yes, and once the work was done and shown, it was not just about me and Rochelle anymore. Like my story might be a silly one to share with the song but Rochelle’s is really rich, and also, I like to think about those people who might say “I remember this song”, and can share their own memories as well. I like what you just said about even someone who had never heard the song before, being able to access it through the narrative. So, it means that it is not just the song that evokes emotion and opens people’s hearts and feelings...

PK: Yes, and also because the song plays in a loop throughout the work, you sit there and you start reading the story as it unfolds, but the music keeps repeating over and over. As a viewer, you add all these layers on top of the music; it’s a nice way to make the song richer for everybody. And actually, I heard the song for the first time in the film In The Mood of Love (2000) but of course I didn't know anything about it then.

AR: I have used two versions of the song in my work – the version from In the Mood for Loveand the version that speaks to my experience as a gay man, which is the original recording of ‘Bengawan Solo’. Actually, [in that film] they made it into a love song. I think the film is very poignant, every time I watch it, it always gives me tears because it’s such a symbol really, about the people who lived there peacefully, and then it becomes kind of actively related with other knowledge – a cruelty of the world and colonization and so on. The land has been there for thousands and thousands of years, and on it people live and die, live and die, live and die, and they leave traces of their memories in the land and for me it’s beautiful.

PK: Yes, I think so too, and you are opening up with this really personal story, which in a way makes you vulnerable. And this is a starting point that I appreciate a lot, explaining how you discovered that you’re gay and so on, and how you become conscious of this through the romance that this song embodies for you, which adds such an emotional layer to it.

AR: And that works because I made the work specifically for Indonesia, and because if you’re gay in a Muslim country, it is very difficult, and I had a very difficult life. To share the work as an Indonesian gay Muslim was to give those feelings space, and I wanted to show the audience that they could maybe share in this level of intimacy between myself as an artist and them as the audience, through the song.

PK: You’re making it possible to expand this song, which is from Indonesia and everybody there will have their own personal connotations of it. But through opening it up and to align it with love as well is expanding the context of the song once more.

AR: It’s not only about being gay as well, I mean love as it is for all human beings…

PK: And acceptance, in a way.

AR: Like when Rochelle talks about Gusta – “Gusta is the almighty”, and Gusta doesn’t have gender – Gusta could be anything.

PK: Especially when Rochelle talks about her father, and how when he got older his ego wasn’t in the way anymore. I found that really interesting, because one could argue that when people are strongly against something, or stuck in their ways, it’s mostly because their pride is in their way. Whereas in your work ‘Bengawan Solo’, there are two narratives woven into each other and also visually, you’re surrounded by a kind of orchestra – as a viewer you feel as if you are almost facing a community.

AR: Yeah, it’s not a movie – I mean, it works in the way that we are using this type of virtual immersion to convince people, so it’s like the narrative is going on inside someone’s head.

PK: Yes, and I’m happy we get to see it here in Frankfurt. Songs are good tools to get people’s attention.

AR: It’s really that simple, yes? Because I have been working with moving image for many years and it was always different from recreating an event as a film, because it’s about how to transform it – because I always think that nothing can replace reality, and once the moment has passed and you want to go back to it, it will already have layers that weren’t there before. But I have been thinking about how to make such a recreation into something more transparent, and so for me music is about representing reality in a different way. In one sense, music is just music, but as with this song – it was created in 1940s and already had all these historical resonances, and so all these years later it is not just about the original song itself but all the layers of the spheres that the song has passed through. I think that’s enough – Bengawan Solo has its own content and to allow this content to appear in the current contemporary moment, I think this is really important.

PK: What I also like, is when you first sit down in front of the work, in a way you just read the texts. Yes, you encounter these different musicians and the singer, but for me it was kind of like going on a story ride, you know? Because as you describe the river and what happened, it’s like this storytelling moment that transforms the viewer into a child that listens and soaks everything up and from there you go on throughout the work. And somehow the story isn’t closed, which is really nice.

AR: Yeah. That’s great. I’m planning to do a new work in Berlin next year and I hope to add some other pieces.

PK: That sounds really interesting.

AR: And you know, I wasn’t quite sure about my way of making work. I mean, as a person growing up in Thailand, in that region the majority of our knowledge is not that strong, so to speak, it’s not that constructed like in Western countries. I liked conceptual work when I was young, I found it really thoughtful, but I mean we weren’t really into nature. And also, in our culture we never separate body and soul, body and spirit. A person is never separate from God. It was almost like Joseph Beuys but it was not this constructed idea. It was just in the nature of the people who lived there. It’s both a bad thing and a good thing. The bad thing was people prayed to the tree for good luck and so many outside people said that this is so Barbarian or something, but still others have attached themselves to nature, and for them they will never separate themselves from the earth, from the trees, from the river. Deep down they believe that one day they will go back to the river, to the earth, to the trees again and I have never disregarded this. I think this is how we communicate with things and a vantage point I could appreciate. I mean, not just to treat reality as a source material to reproduce in art.

PK: That adds another dimension to the river in your work, because the river is symbolic of an eternity, but I think besides it being, you know, old-fashioned to prey to a tree, it still shows a kind of respect for nature and its power when you’re surrounded by it.

AR: There’s also one poem by an Indonesian poet, which is about a person that wants to walk across the river and he is hesitating because he sees his relative’s spirit fill up that water and he cannot step into the river because of his ancestor.

PK: There is so much additional information for your work.

AR: Because the process is so complex, all the information, research, and so on. My work that was at documenta 14 246247596248914102516 … And then there were none(2017) too – that one was super rich too, so much information – this, this, this – we have tons of information…

From time immemorial, one of humankind’s most important missions has been to preserve knowledge. We do so not only by passing on oral traditions to subsequent generations, but above all with memory institutions. This collective term unites all those institutions whose goal is to preserve and convey knowledge. While libraries and archives may come to mind first, they also include museums. They are places that administer bits of contemporary evidence and seek to protect what constitutes the identity of a society: its cultural heritage.

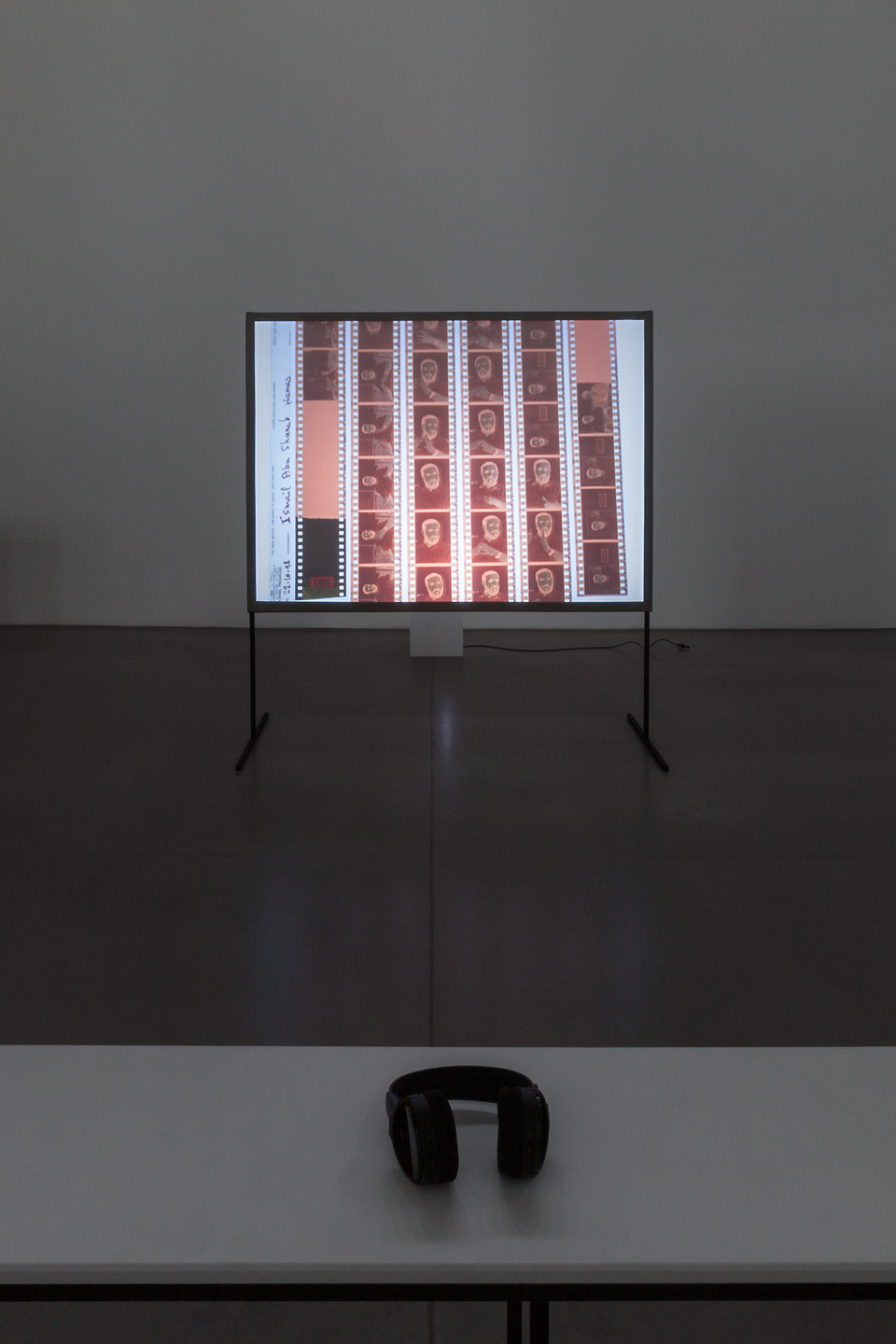

Sirah Foighel Brutman & Eitan Efrat, Printed Matter, Installation view, Slide show, 29.04.–11.06.2017, Portikus. Photo: Helena Schlichting.

All of these institutions do their part to ensure that we do not forget. Indeed, they function as a collective memory. But like personal, individual memories, there are events that we like to think back on in pride as well as unpleasant events that we tend to forget. Psychoanalysis refers to this process as repression. While the ordinary act of forgetting unconsciously stores irrelevant information in favor of the more important, with repression content is deliberately excluded from memory in order to avoid unpleasant emotions. Repression is thus a natural self-defense mechanism. But what happens when memory institutions also make use of this strategy? When those institutions in particular repress inconvenient truths that nevertheless are regarded as the guarantor of truth per se?

Michel Foucault robbed the archive of its innocence in the late 1960s. He pointed out that this place does not collect truths, but constructs them. Under the guise of objectivity, facts are first produced in such a way that each archived document implies a multitude of others that have not been included in the selection.1 If institutions such as archives and museums serve to administer both history and the present, we must be made aware that power structures within these institutions are ultimately responsible for which contents are rated as valuable and which are pushed into the cultural subconscious. Hence, cultural memory is no more than a canon.

Sirah Foighel Brutman & Eitan Efrat, Printed Matter (Still), 2011.

Those who are inscribed in this canon will not be forgotten. They are remembered. Just as Hanne Foighel remembers her partner André Brutmann. In the video Printed Matter (2011) by Sirah Foighel Brutmann and Eitan Efrat, contact prints are placed on a light box while a friendly female voice comments on the negatives. The images belong to the artist’s father, the voice is that of her mother. Until his death in 2002, André Brutmann was a sought-after press photographer who followed the Israel-Palestine conflict in particular for decades with his camera. Yet the contact prints show not only pictures of abandoned cities and rebellions, but also pictures of his family. Brutmann’s archive is not just that of a photographer, but also of a father. The same rolls of film contain images of heads of state, funerals and children’s birthday parties. While the artist’s mother gets nostalgic when looking at the family photos – commenting on pictures of herself in a bathing suit by laughing, “this doesn’t belong here at all” – her voice often drops when she sees the photographs that Brutmann shot for the public.

Uneasiness accompanies these photographs. The memory of these moments produces silence. The manner in which Foighel talks about the pictures seems not only to provide information about the past, but also about the present. The memories of the political conflicts in the 1990s seem to dissolve mostly in silence because today there is still no solution for them in sight. Rather, the photographs seem to be a historical narrative of our present in that they remind the viewer of conflicts whose traces are still visible today.

“The photograph does not necessarily say what is no longer, but only and for certain what has been. This distinction is decisive. In front of a photograph, our consciousness does not necessarily take the nostalgic path of memory (...), [but] the path of certainty: the photograph’s essence is to ratify what it represents.” 2 In photography, Roland Barthes sees only the image of a present that has already occurred, which can say nothing about a before or an after. In the same way, Sirah Foighel Brutmann and Eitan Efrat seem to argue with Printed Matter not only by showing visual material, but having a contemporary witness comment and reflect it on the auditory level. They thus inscribe the archive of André Brutmann into the present rather than leaving it to remain in the past.

Sirah Foighel Brutman & Eitan Efrat, Printed Matter (Excerpt), 2011.

But unlike photography, memory is imprecise. It remains a fragment that can never be pieced together as one overall picture.3 Memory can muddle up data; it can confuse places and people. It can only remember significant events and even those can once again be forgotten. Moreover, it can repress. For this reason, it is especially the interplay of testimony and witness that can generate meaning at all. This connection precedes what we call truth and even then, it must always be verified.

Translation by Faith Ann Gibson

In many ways, the 1960s were revolutionary and groundbreaking for the visual arts. It is therefore not surprising that artists’ use of many previously unconventional materials in the work process originated or experienced a great upsurge during that decade in particular. Artistic boundaries disappeared or were re-explored and materials such as textiles soon became “autonomous artistic materials.”1

One of the best-known pioneers of this development was surely the German artist Joseph Beuys, who acquired an international reputation not least with a focus on the materials of felt and fat. Beuys’s American colleague Robert Morris is also known for his work with felt, although the two artists’ underlying intentions in their work with the material differed greatly.

The fact that textiles played a rather marginal role in art for quite some time before this can also be explained from a technological point of view. Ultimately, a certain type of machine was needed to weave large-scale ornaments and complicated textile designs. Although Joseph-Marie Jacquard (1752-1834) demonstrated his famous loom for the first time in 1801, for a long time this technique was by no means freely accessible or it was horrendously expensive, making it difficult for artists to produce certain fabrics at all.

Jacquard looms are mainly characterized by the fact that they were the first of their kind that wove on the basis of punch cards, thus making complicated patterns possible. Each warp could thus be worked individually or in a small group per weft, which was impossible with previous mechanical models. “Acquired Nationalities” by Rosella Biscotti in the exhibition House of Commons at Portikus showed that this methodology is still relevant in the artistic production process.

Jacquard loom, filmed at Paisley Museum (© National Museums Scotland)

Conceived as part of the 10 x 10 series, Biscotti works with demographic data from the Belgian census of 2001 and the national registry (January 1, 2006), transforms and models them with the help of programmed Excel calculation models to then visualize them on textiles with a computer-controlled jacquard loom. As for content, the artist is particularly interested in the tension between the individual in society and a statistical structure that is indispensable for the allegedly objective description of the same within political institutions. The result is an exciting interaction consisting of demographic data, its processing and visualization in 25 different shades of gray on textile.

Rossella Biscotti, Aquired Nationalities, 2014, KADIST collection, Installation view, House of Commons, 03.12.2016–29.01.2017, Portikus, Frankfurt/Main, Photo: Helena Schlichting

In addition to the work of Rosella Biscotti, other recent Frankfurt exhibitions also showed works with a focus on textiles. One example is Willem de Rooij’s large woven pictures from the weavings series (2011-2014) in the exhibition Willem de Rooij. Entitled at the Museum of Modern Art – MMK 2. Since 2009, de Rooij has been producing the works in the Henni Jaensch-Zeymer hand weaving plant near Berlin. The dimensions of the works are always based directly on the capabilities and techniques of the looms. The artist compares the crossing of threads running in two different directions with terms such as opposition, contrast, transition and nuance. Some of the resulting textiles are highly reminiscent of monochrome paintings, but on closer examination the seemingly monochrome fabric reveals at least two color nuances.

Willem de Rooij, Taping Precognitive Tribes, 2012 , Courtesy: Friedrich Christian Flick, Photo: Axel Schnider, Quelle: Mousse Magazine)

Similarly, the artist Thomas Bayrle, who lives and works in Frankfurt, deals with textiles, or, more precisely, with ornamental pictures and the principle of the serial. With an eye for subjects from pop culture, Bayrle, who is a trained weaver, is particularly interested in “the relationship between the individual thread and the whole fabric”2 and compares this structure with the relationship of the individual with the collective or with society. In addition, the artist has also revealed his skills in applied art, as his designs for the world-famous fashion label Clemens en August show, which were also shown in the 2008 retrospective of his work at the Francesca Pia gallery.

Thomas Bayrle, All-in-One, Installation view, WIELS Contemporary Art Centre, 09.02 – 12.05.2013, Brussels, 2013. Quelle: WIELS

As we see, textile works are neither superficial, as an association with the fashion world might perhaps suggest, nor do they represent a mundane craft. Rather, the mere complexity of the different materials proves that textile is an ideal medium to describe both individual stories and social contexts, or to even interweave the two themes.

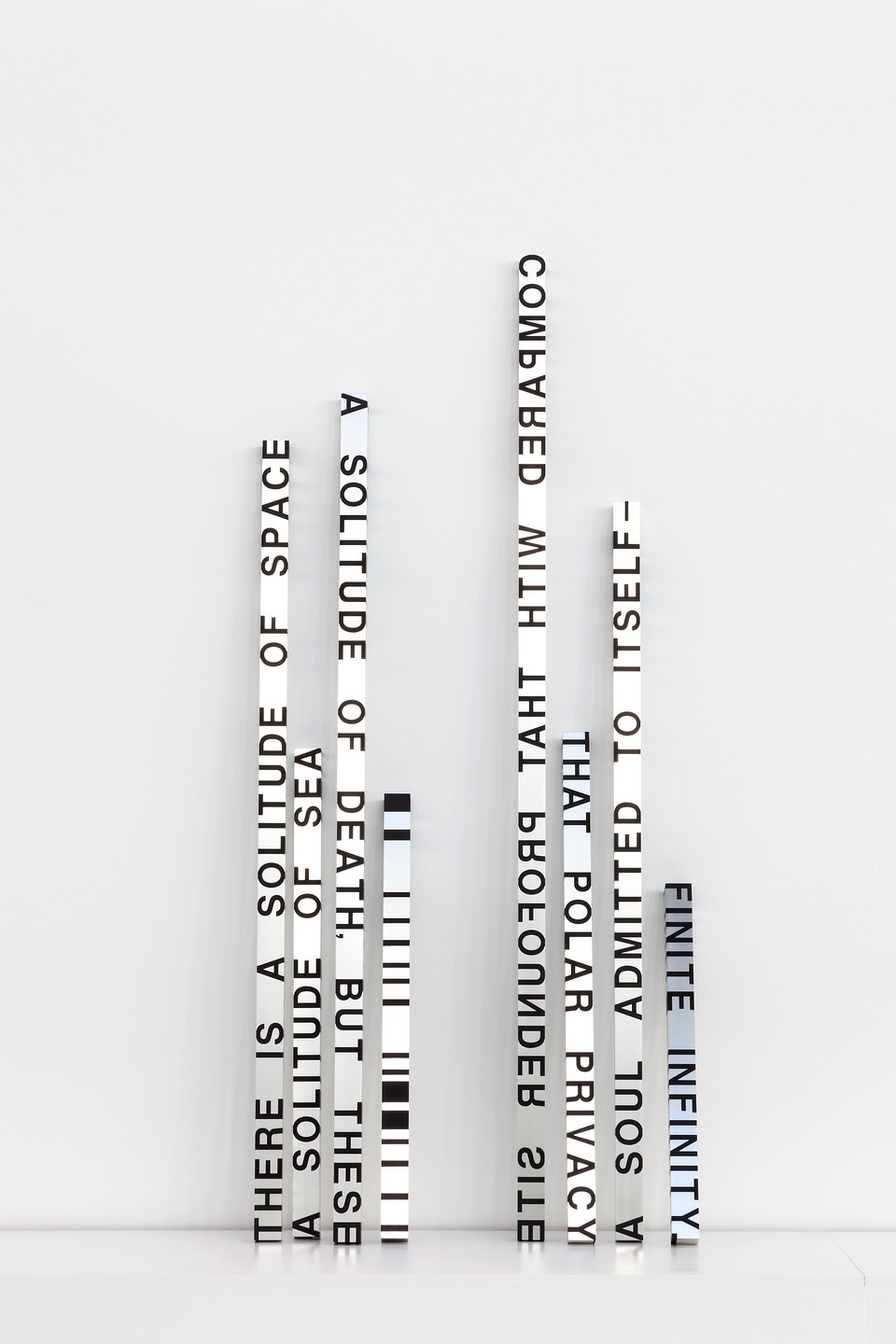

Eight square aluminium bars of different lengths lean – at regular intervals – on the white wall of Portikus. The smooth polished surface reflects the light and the surroundings, wrapping it in a silvery white shimmer. On each of the long sides of the bars, a verse of poem number 1695 by Emily Dickinson, “There is a Solitude of Space,” can be read in black, vinyl, sans serif capital letters:

THERE IS A SOLITUDE OF SPACE

A SOLITUDE OF SEA

A SOLITUDE OF DEATH, BUT THESE

SOCIETY SHALL BE

COMPARED WITH THAT PROFOUNDER SITE

THAT POLAR PRIVACY

A SOUL ADMITTED TO ITSELF—

FINITE INFINITY. 1

Roni Horn, When Dickinson Shut Her Eyes: No. 1695 (There is a Solitude of Space), 1993, Installation view, House of Commons, 03.12.2016–29.01.2017, Portikus, Frankfurt/Main, Foto: Helena Schlichting.

The words of the nineteenth-century poet, who as a teenager had already retreated to the house of her parents in Amherst, Massachusetts, and while living as a recluse wrote 1775 poems. Her lines are forced into the vertical by artist Roni Horn and resound modestly in the exhibition space. In the 1990s, the artist developed a series of sculptural works entitled When Dickinson Shut Her Eyes that are directly related to Emily Dickinson’s poetic work, embodying and re-“enacting” her poems. The works question the exchange between language, object, and viewer and, in their calm, uniform appearance, promote the extension of established patterns of thought.

Roni Horn’s industrially manufactured aluminium bars interlink text and objects in many ways. They line up alongside one another like lines of poetry cut out of a book. Their metallic surfaces reflect Portikus’ upper wall and ceiling segments while assuming the white colour of a paper background. Where the letters touch the edges, they continue as markings. They thus surround the shaft of the bar and convey the image of inflated letters made of deeply absorbed ink. Here the two-dimensional medium of writing surrounds the three-dimensional body of the individual sculptures. Thus, the work of Roni Horn shimmers between two correlations of text-become-object: On the one hand, the lengths of the lines determine the exact size of each single sculpture while the multi-perspective characters emerge from their background; on the other hand, they are bound and tied to the carrier, thereby underscoring their formal correlation and dependence.

Roni Horn, When Dickinson Shut Her Eyes: No. 1695 (There is a Solitude of Space), 1993, Installation view, House of Commons, 03.12.2016–29.01.2017, Portikus, Frankfurt/Main, Foto: Helena Schlichting.

Each bar is also a self-contained and closed object. However, one of the middle bars arouses curiosity. It is positioned so that the side with the writing is turned towards the gap between the objects making the line “SOCIETY SHALL BE” indecipherable from the front. Since at this point the communicative function of writing dissolves in favour of its graphic qualities, a tense relationship between the objectness and the textuality results. The gaps become associative open spaces. They open our view to the white wall behind them, and, like reading between lines, allow us to search for further levels of interpretation.

As viewers, we are challenged in a special way by the characteristic of the text-object-relation. The reading direction and the course of the letters are always vertically oriented, so that the bars form links in a literary-poetic chain; a series of sentences whose syntax is disturbed by the different orientation of the text. We are urged to read with a constant change of perspective: at times from the bottom to the top, then turned around, and then mirrored. In this way, the work breaks with our usual, static reading behaviour. To grasp the sentences in their completeness, our bodies are forced to move. Disagreement arises between distance and proximity. On the one hand, we physically adapt to the direction of the writing while reading, but at the same time this specific interaction alienates our reading flow.

Roni Horn materializes the words of Emily Dickinson and translates them into a physical experience. She confronts us with a static corporeality that demands that we move. While quietly pacing alongside the objects, the sentences mentally shape themselves into a whole, creating the projection surface for a variety of readings and perspectives on the work. Standstill and movement, language and form flow together to a spatial and temporal experience within which the units dissolve. The artist thus creates a situation in which associative mental play and physical motion connect.

Translated by Faith Ann Gibson

Skin covers the surface of the human body, shrinking or expanding as the body moves and bearing the marks of its actions and the impacts it has suffered. Objects that cling to the skin, that are used or worn by the body, influence its posture and the way it moves and conversely adapt (or are adapted) to its characteristic movements. Clothes, shoes, furniture, and prostheses add to the body’s repertoire of forms and functions. They endow it with abilities that, in and of itself, it possesses only to a degree; for example, they enable it to withstand cold without feeling it, to sit elevated above the floor, or to walk with a single leg. Even when they are not in use, these objects evince the traces of their application: they are virtual images of their wearer.

The pedestal is a body in space. When it appears in the context of an art exhibition and supports an object, that is a choice made by third parties (artists/curators). This choice stands for the duration of its presentation. It prompts contact between two bodies, the supporting body and the one being supported. The pedestal adds several functions to the object to be supported: it sets it apart from the space around it and elevates it; the floor on which the beholder stands is no longer the ground on which the object rests, this provokes a distance that brings the perception of its surface into focus. That distance elevates the object both in fact and in the idea. Things reduced to the purpose of being beheld become (virtually) untouchable and no longer belong to the realm of objects of utility.

Edgar Degas, Petite danseuse de quatorze ans, 1878/1881, by M.T. Abraham Center - Provided by copyright owner of both photograph and artwork, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

How present may a pedestal be in the framework of a presentation? It depends on how self-contained the work of art it supports is, or in other words, how strongly it insists, by virtue of its facture, on the difference that sets it apart from the space around it. When object and pedestal make their presence felt with equal force, the pedestal becomes part of the work of art.

Michelangelo Pistoletto, Vetrina-Specchio, 1966

However, there are art objects that do not rest on a pedestal and nonetheless engender the distance from the beholder required to be perceived as untouchable works of art. A higher degree of autonomy is attributed to works that produce this effect by dint of their own constitution rather than by virtue of their being installed on pedestals. When their surface is in direct contact with the floor they share with the beholder, they do not require any support.

John McCracken, Minnesota, 1989

The body of the pedestal can manifest itself in a variety of ways. The more “normal” it is—the more its form follows its function as a humble support—the more it will tend to become invisible. The further it deviates from this subjective standard, the more its presence will be felt. Factors that play into its visibility or invisibility include its proportions, form, materiality, and surface. When a pedestal does not support an object, its surface becomes a projection screen. The more it departs with regard to these traits from what we are used to perceiving as pedestals, the more it will become an autonomous sculpture. An object of utility then metamorphoses into an object of contemplation. The distinction is not clear-cut. Transitional phenomena range from a sort of phantom pain making the absence of an object on the pedestal so keenly felt that its likeness seems almost graspable, to the sense of formal saturation evoked by the appearance of the pedestal itself.

Shahryar Nashat, Chômage Technique (A,B,C,D,F,G,H), 2016

Shahryar Nashat’s work Chômage Technique consists of pedestals painted in a rose color and installed on chair-like stands, where they seem to be basking in the pink light filling the Portikus. They face Nashat’s video Present Sore, which shows bodies in action as well as rigid poses in brief but intense sequences. The camera pans over flawless or bruised skin surfaces, focusing on the points where they come into contact with apparel, bandages, and prostheses. Then the video gingerly approaches one of Paul Thek’s Meat Pieces, with cables and hoses protruding from it; it is repeatedly interrupted by a rendering of a pink-dappled menhir that lingers on the screen longer and longer. The small pedestals dispassionately observe the goings-on in the realm of things: relieved of their function, they shall not be made to support any of it.

Translation: Gerrit Jackson

To the exhibiton by Shahryar Nashat

Marina Rüdiger, Master of Fine Arts & Bachelor of Art History (Kunsthochschule Kassel), currently studies curatorial studies, a master’s programme at the Staatliche Hochschule für Bildende Künste – Städelschule and Goethe University Frankfurt and works for Galerie Bärbel Grässlin in Frankfurt.

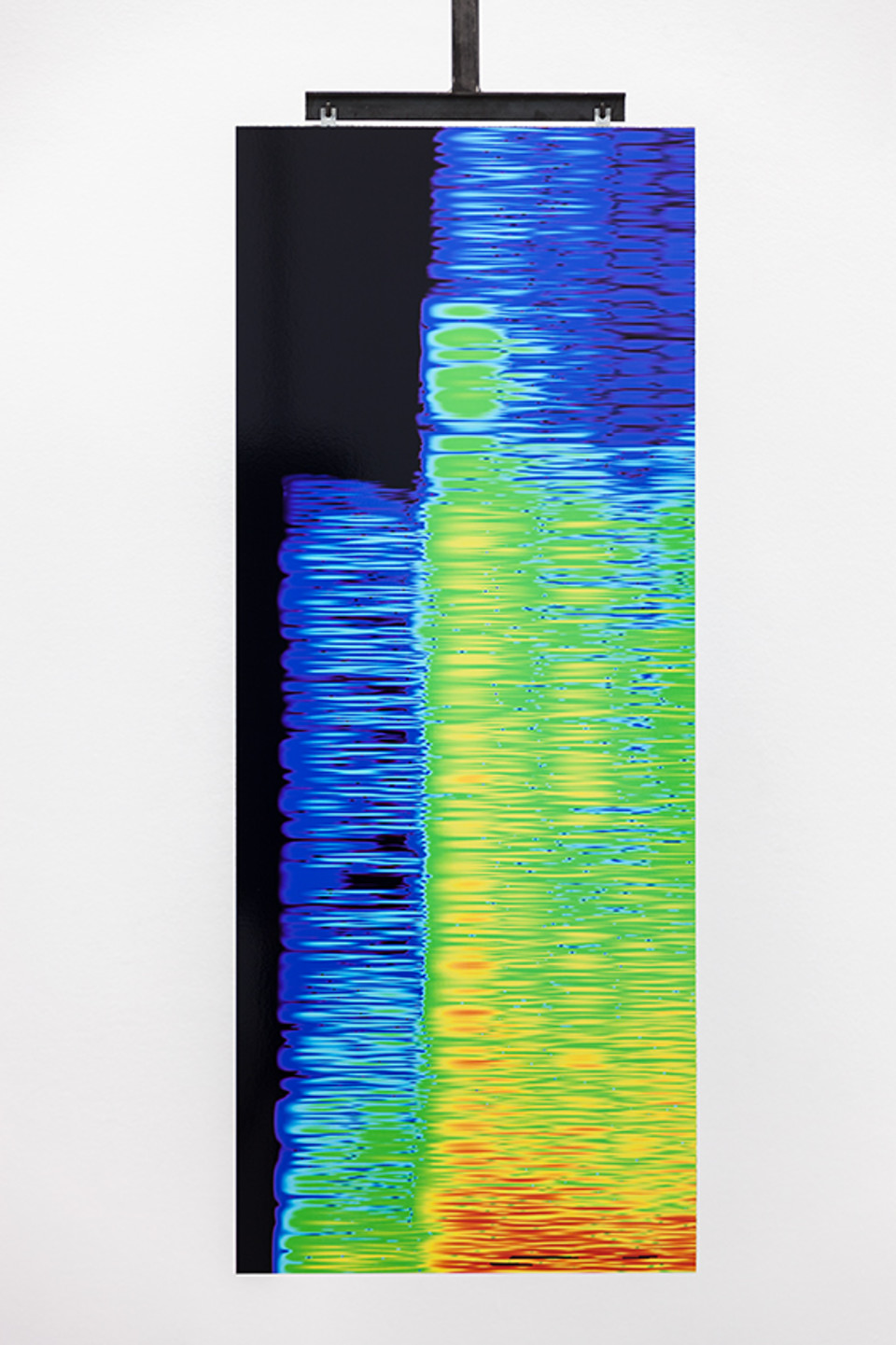

Spotting the Shottspotter: photograph of Shotspotter microphone installed on the top of a street lamp. Courtesy of the artist.

In December 2014, new audio evidence emerged that captured the moment when unarmed teenager Michael Brown was shot to death in Ferguson, Missouri that August. The audio was submitted by an anonymous man who incidentally caught the moment of the shooting as he was recording and sending a private voice message from his phone using the Glide app. He only realised much later the significance of the gunshots he had accidentally recorded.

In this recording it is audible that Brown's murderer, a police officer by the name of Darren Wilson, fired his gun ten times. Six of these shots hit Brown, mostly in the head (all above the torso). And yet there is another and unexpected violence that is captured in this recording – one that, whether presented on CNN or to the grand jury, listeners were asked to ignore. While both defence and prosecution provided forensic audio experts to provide their own accounts about the gun shots that could be heard in the background of this recording, neither realised that the greater Police violence enacted upon the residents of Ferguson and many other African-American neighbourhoods in the United States, was in the foreground, clear for all to hear.

This is the recording transcribed with both the foreground and background sounds included:

"You are pretty. [6 gun shots]. You're so fine. Just going over some of your videos. [gun shot] H[gun shot]ow c[gun shot]an I f[gun shot]orget?"

Dr. Robert Showen was one of the key expert listeners in this case. His analysis of the gunshots centred mostly on the echo they created. Using the impulse sounds of the shots and their reflection off nearby walls, he was able to define the space around the shooter. As each echo of each shot was very similar in sound, it meant that a conclusion could be drawn that the murderer was stationary and stayed more or less in one place while he was firing the shots. This evidence corroborated some eyewitness testimony and was also key to denying the veracity of other contradicting accounts. Technicalities that amounted in the end to a greater body of evidence that concluded that unarmed Michael Brown was charging at the officer and that the officer was therefore acting in self-defence when he repeatedly shot Brown in the head.

The expertise of Dr. Robert Showen was called upon because of his extensive experience of working with gun shot sounds as echo location instruments. Showen is the founder and creator of ShotSpotter™, a gunshot detection and location service, which works by installing microphones throughout a neighbourhood to listen for sounds from the street that might be gunfire. When the microphones detect a loud bang, they automatically triangulate where this sound is coming from. The information is algorithmically analysed against a huge database of loud bang sounds to quickly verify if the sound registered is indeed a gunshot. If it decides that the sound is gunfire, it sends the location of the gunfire to the Police Department. This is on average accurate within thirty feet of where the shot happened. ShotSpotter™ system of microphones is now installed in eighty "troubled" neighbourhoods across the United States. They have aspirations to cross the Atlantic, having now installed systems in South Africa and, after the recent attacks in Paris (November 2015), they saw the opportunity to make themselves available on the European market.

Dr. Robert Showen told me in an interview that ShotSpotter™ microphones are typically placed on the rooftops of buildings so that one can "listen to the horizon". "So they are mostly installed on private property?", I asked. His response was: "Yes we went out with the police officers and knocked on doors and asked if the people would allow us to put a sensor on their building to help protect the community from gunfire, practically everyone agreed [...] everyone was just willing to donate their roof for the benefit of the community". Showen's statement that "everyone was willing" seemed contradictory with ShotSpotter™, whose whole rhetoric was constructed on its necessity as a security infrastructure, based on the fact that the communities affected by gun crime were made up of unreliable witnesses who failed to report more than eighty percent of the gun shots they had heard. The idea then is that ShotSpotter™ would replace these unfaithful ears with law abiding microphones and be able to algorithmically detect eighty percent of gunshots that went previously unreported. Showen says: "Our sensors' microphone sensitivity is almost identical to what is on a cellphone and a speakerphone". But the human hearing capacity is in general much more sensitive and adapted to reading sounds than a cell phone microphone placed on a rooftop. Therefore the issue is not that people don't hear the gun shots and the microphones do, but rather that people hear the gunshots and choose not to report them to the police. This startlingly high figure of unreported incidents suggests that, as in the case of Michael Brown and hundreds more since, the police can be more dangerous, more racist and more trigger-happy than the alternative. Showen seems oblivious to this idea when he speaks of the brutal inauguration ceremony that happens in each community when ShotSpotter™ is installed: "When we install a system, we have the police go out and shoot and we see the accuracy and the sensitivity of our system".